Written by OneGuild Institute

For people with type 1 diabetes (T1D), movement can be both medicine and risk. Exercise — vital for long-term health — is often unpredictable in its effects on blood glucose levels. A brisk walk might cause a drop. A harder workout? It might trigger a spike. This variability has left many hesitant to move at all.

But what if your body could tell you — ahead of time — what it’s going to do?

Dr. Elliot Botvinick and his team at the University of California, Irvine (UCI) are working on just that. In a clinical study funded by the Helmsley Charitable Trust, they’re testing a wearable device that doesn’t just monitor glucose, but reads lactate dynamics during and after exercise — offering a more complete metabolic snapshot than glucose alone.

The hypothesis: by combining glucose and lactate sensing, the device could predict blood sugar trends up to an hour or more into the future, helping individuals adjust insulin delivery or carbohydrate intake before problems arise.

“For people with T1D, intense exercise can lead to rapid hyperglycemia, whereas moderate exercise tends to lower blood glucose,” Dr. Botvinick explains. “This unpredictability discourages many not to exercise, which is particularly dangerous in the long term.”

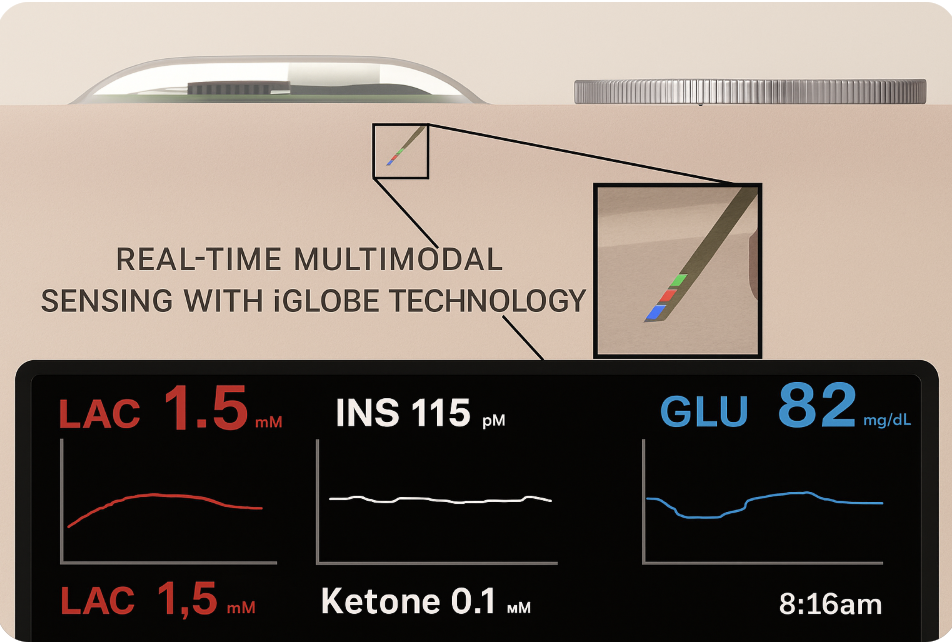

Their custom fiber-based sensor — about a third of a millimeter wide — sits just under the skin and connects to a wearable receiver. The ultimate goal: provide real-time guidance to insulin pumps, allowing them to automatically adjust dosing during activity or alert the wearer when to take action.

The technology, part of a broader platform called iGLOBE, is being expanded to measure insulin and ketone levels as well — creating a single-site, multi-analyte window into metabolic health. And beyond the lab, this work may be headed toward commercialization, with the team exploring a possible spinout company.

Wearable devices can help people with diabetes walk with more confidence, backed by real-time insights.

The approach is part of a broader movement to make diabetes care more adaptive, personalized, and movement-friendly. Instead of asking people to reduce risk by avoiding exercise, Dr. Botvinick’s work aims to embrace the body in motion — and meet it with the right information, at the right time.

For people with T1D, that could mean more freedom, more confidence — and more movement.

For those interested in learning more, Dr. Botvinick has presented aspects of this innovation in public forums. While these videos do not include the latest findings, they offer helpful context on the foundational science behind the work:

– Presentation at Helmsley Scientific Meeting

– Presentation to A Different Group

__________________________________________

➝ Read Next: AI in Limb Threatening Ischemia: A New Lens on Risk and Precision